How We Work | Lead Stories

How we find claims and stories to fact check

Lead Stories looks for claims and stories to fact check using several tools and methods, here are the most important ones:

- Our own Trendolizer™ engine

- Google Trends

- Facebook's tool for Fact Checkers

- TweetDeck

- CrowdTangle

- Reader tips

Trendolizer

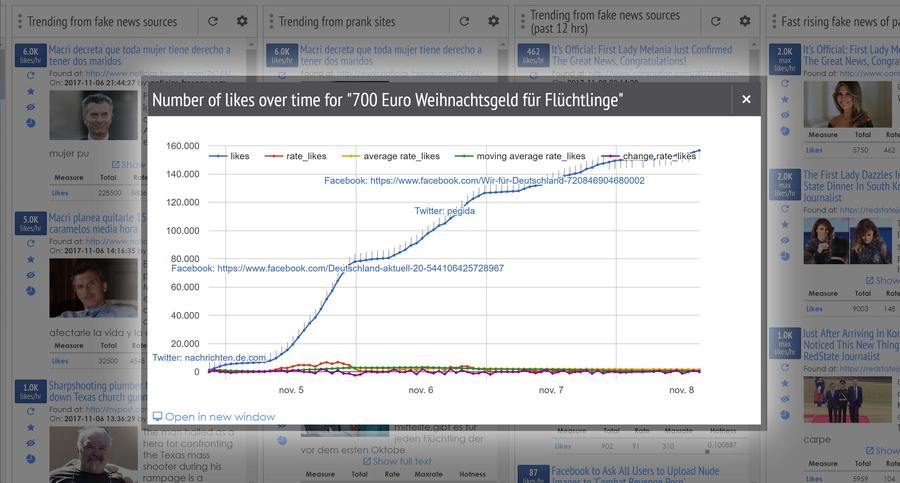

Lead Stories created the Trendolizer™ engine to monitor the internet and look for newly trending content. It can measure the engagement rate (likes, views, comments, retweets etc.) of links, images and videos appearing on various platforms (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, TikTok...) and gives us an overview of what is currently going viral.

(screenshot from our Trendolizer™ dashboard)

We use Trendolizer to monitor the internet for viral content in general but also look at popular content from specific sites that have posted false information in the past, along with viral content matching keywords and phrases associated with false narratives or conspiracy theories.

Google Trends

We use Google Trends daily to check which search queries related to fact checking phrases ("fake news", "fact check" etc.) are popular on Google. This usually indicates people are searching for answers about a particular story because they have doubts about the veracity.

Facebook's tool for fact checkers

Lead Stories is part of Facebook's Partnership with Third Party Fact Checkers and as such we get access to lists of content that has been flagged as potential candidates for fact checking (via a custom tool for fact checkers provided by Facebook) . Note that Lead Stories is free to pick items from that list or to ignore them, Facebook does not tell us which stories we should do.

TweetDeck

During breaking news events Lead Stories often also uses TweetDeck, a tool provided by Twitter, to rapidly scan Twitter for viral content about specific events (violent incidents, political events, protests, breaking news...)

CrowdTangle

In order to determine the virality of certain links we also use CrowdTangle, a Facebook-owned tool that provides statistics on social engagement on Facebook, Reddit and Twitter.

Reader Tips

Readers can always contact us via our contact page if they have a tip about an online story that is potentially false and harmful. In practice we get very few tips like this but we would love to get more.

How we select claims and stories to fact check

On a typical day we will look for the most trending stories/videos/posts/... with these tools and pick the ones that meet following criteria:

- They make a claim that can be checked (i.e. no pure opinions, predictions, vague statements or prophecies). Note we include claims that could be checked theoretically with access to the right evidence or witnesses but where this very hard or impossible in practice (quotes from closed meetings, insider information...).

- They are harmful to someone. We interpret "harmful" quite broadly here, it can include anything where there is a risk of: negative health impacts, reputational damage, political decisions based on inaccurate information, minimizing or exaggerating real problems, emotional impact over fictional stories presented as real, fraudsters profiting from spreading false info, financial loss, distorted understanding of current events, people getting wrongly blamed for things, false evidence being used to support larger conspiracy theories...

- They are (likely to go) viral or contain a claim that has gone viral in the past. Note that we don't use fixed numerical cut-off rates (i.e. it must have more than x likes or y views), we tend to look more at the relative ranking (i.e. "this is the most viewed video about this particular conspiracy" or "this is the most popular fact checking related Google search today") and we sometimes also look at the number of places a claim is appearing (hundreds of tweets with the same image and one image tweet with hundreds of retweets are both valid reasons to check out the image). To determine which items are "likely" to go viral we look at short term steep increases in engagement and the audience size of the source making or spreading the claim (an Instagram page with a million followers vs. an obscure blog read by almost nobody).

- They are relevant to or affecting a U.S. audience. We will generally leave the internal politics, hoaxes and harmful misinfo going viral in other countries to the fact checkers in those countries unless there is a U.S. angle or the same claims are also spreading in America.

Generally we prioritize stories related to current events and new and never before seen claims but we also tackle older claims sometimes, especially if they have a tendency to keep coming back periodically (think old hoax articles that keep getting reposted to new sites by financially motivated spammers or fake quotes attributed to a politician that keep showing up whenever that person is in the news).

We do not take political slant into consideration when choosing what to check. We check claims that harm (or benefit) people, causes and groups all over the political spectrum.

We do sometimes check claims that originated on satire websites or that are satirical in nature but only in cases where it seems significant numbers of people believe it is real. You can see our Satire Policy here.

Reader tips are judged by the same criteria listed above: if we get sent claims that are uncheckable, harmless or not very widespread there is very little chance we will follow up on them. Conversely, a concrete, harmful and viral story will get our attention.

One of the aims of our fact checking is to help stop or slow down the spread of trending false information. This means we rarely publish fact checks to point out something is indeed true: if the truth is going viral by itself we are quite happy to leave it alone.

How we fact check claims and stories

Methodology

Each claim is different and not all of them require the same approach. Generally we first try to reframe the claim as a question ("Is it true that X?") and then our goal is to provide an answer to that question along with the reason and the available evidence.

There are questions we usually ask and try to answer in order to be able to say if a claim is true or not (although not all of them may apply in all situations):

- Where did the claim originally come from and is there evidence for that orgin? If something first appeared in a fictional setting or in a satirical piece it is quite unlikely to be true. In some cases it is unfortunately not possible to find the original source.

- If the source is known: what evidence does it cite and does it support the claim? (If an article says "New study says X", does the study actually say X?)

- Are there logical inconsistencies or unwarranted leaps and assumptions about the evidence in the claim? ("Person X was once seen with person Y and there is a photo of it, that must mean they are both involved in an elaborate scheme!")

- Are there alternate explanations for the evidence? ("Person X was arresting person Y in the photo", "The photo was digitally manipulated", "The photo does not actually show person X or Y"...)

- If a source claims to have inside or confidential information, is it likely/possible they would have it? ("Would a random guy on the internet have access to Top Secret higly classified intel from the CIA? If so: how and why isn't such a security lapse not the a bigger story here?")

- Is the evidence from trustworthy official or reputable scientific sources (or is there such evidence available)? We tend to look for official statistics with a known methodology that have been collected over longer periods of time and peer-reviewed scientific articles about double-blind studies with large sample sizes. Pre-prints, non reviewed studies, press releases with no link to a full study, survey results, studies with very small sample sizes, publications from special interest groups etc. have far less value as evidence or support for a claim.

- Can the people named in the story be contacted for comment? This is unfortunately not always possible: there might not be any contact info, they might be anonymous or they might be hard to reach. We try anyway if it is important for checking the truth of a claim (if there is video from multiple angles of someone doing something and there are several reliable witnesses there is little value in asking "did you do it?").

- Are there experts or local sources who can confirm or disprove the claim?

- Does technical analysis of the source and/or evidence show proof of tampering, editing or manipulation?

- Does the claim or the evidence match with the record? ("Does this quote really occur in this recorded interview?", "Was this photo really taken on date X in location Y?")

- Does the claim mix things up or cause confusion, intentional or not? (Almost any judge, cop or prison guard in the world can be said to have had "associations with known criminals" and every almost every fireman "has been at the scene of a suspicious fire carrying an axe", that does not mean they are evil or something nefarious was going on.)

Our goal is to serve our readers by publishing an article reliably proving or disproving a claim as quickly as possible. This means we tend to publish as soon as we have collected enough information to confidently make the call but we sometimes continue updating the story while we collect even more supporting evidence or when sources get back to us (more experts/sources calling back, FOIA requests being answered...).

In the (fortunately rare) case where our initial assessment was wrong or when newer evidence requires changes to the conclusion we will update the story in accordance with our Corrections Policy.

Note that in some cases it is impossible to prove or disprove a claim, simply because no good evidence is available. In such cases we will point out there is no evidence we could find for or against the claim and that the person or website that made the original claim is doing so without providing any proof. We will also explain how and where we looked for evidence.

Headlines, thumbnail captions, article structure & our (lack of) rating scale

All our articles generally follow the same structure to allow for easy scanning and to avoid accidentally spreading false information.

We know many people will only ever see our headlines and thumbnail images on social media and that the vast majority of people who see a social media post will not click through to read the full article. Of those who do, many only read the first paragraph.

So we aim to put as much information in the headline, thumbnail image and first paragraph as we can.

Headline

Generally we try to stick as close as possible to the headline of the original article or video or to the text of a meme/tweet/screenshot we are fact checking, but with the addition of the words "Fact Check:" and a capitalized word to negate the meaning (when the original headline or claim is not true).

For example: "This Is An Apple" becomes "Fact Check: This Is NOT An Apple".

If the original headline does not actually contain the main claim being checked by our article we might opt to put the claim in our headline rather than stick too closely to the original headline. For example if the original headline reads "World Shocked By Person X" and the article then talks about something X did not actually do our headline would be "Fact Check: X Did NOT Do Y" instead of "Fact Check: World NOT Shocked By Person X".

Note that we also don't reflexively negate every headline or claim because proving the opposite is sometimes equally impossible or the negated headline has a different meaning than what we intend to say. If the claim is "X Killed Y" and there simply is no evidence either way that X did it or not, it would not be correct to say "X Did NOT Kill Y". In such cases we would say something like "NO Evidence X Killed Y".

And when a headline reads "X Causes Y According to Scientists" and it turns out the scientists did not actually say that, our headline would likely be something like "Scientists Did NOT Say X Causes Y" rather than "X Does NOT Cause Y According To Scientists".

Sometimes multiple negations might be needed to fully explain what is going on: "Fact Check: X NOT Arrested For Doing Y" would still imply X did do Y (but he got away with it) so if X is innocent the headline would be "Fact Check: X NOT Arrested; Did NOT Do Y".

The goal of our headlines is to immediately tell our readers the conclusion of the fact check so that even if they don't read the rest of the article they have not been exposed to false or misleading information. That is also the reason why we don't use question headlines. If someone only sees "Fact Check: Did X Kill Y?" they might still get it stuck in the back of their mind that maybe X really was the murderer of Y or that questions are being asked about it.

Thumbnail captions

Our stories all contain a screenshot of the original post/article/website/tweet/video that made the claim (or at least a representative example of it). This screenshot will have a caption superimposed over it that can contain a maximum of fourteen characters. This captioned image is also the thumbnail image when our stories get shared on social media.

Since the spring of 2020 we ask our writers not to put a summary of the *conclusion* of the fact check in the caption anymore because that information should already be in the headline. So you shouldn't see things like this on recent stories:

- False

- Misleading

- Not True

- Fake

- Hoax

- ...

Instead we ask our writers to boil down and summarize the reason for the conclusion there in one to three words.

Why is there a problem with the claim? Why is X NOT Y?

Some good examples of what the caption can be include:

- "Old Numbers"

- "Photoshop"

- "Missing Info"

- "Still Alive"

- "Scam"

- "Just A Joke"

- "Slowed Video"

- ...

Here is an example for a hypothetical post with the headline "Fact Check: This Is NOT An Apple":

Why is this not an apple? Because it is a banana!

Article structure

Our articles all have the same basic structure:

- A headline that starts with "Fact Check:" and which immediately contains the conclusion of the fact check ("X Did NOT Do Y").

- Introductory paragraph that starts with the claim as a question, directly followed by the answer and a two or three sentence summary of the reason for that answer. ("Did X Do Y? No, that's not true. Video shows Y was at a different place when X happened and local police confirmed this.")

- A Link to the oldest version of the claim or to a representative example of a post making the claim, followed by a short excerpt or a screenshot. ("The claim appeared in an article on site X, published on date Y, titled Z. The story opened...")

- The detailed fact check, listing all the evidence and reasons. Our goal is to provide links to all relevant info so that readers can replicate the fact check for themselves ("Here is an embedded security video... Police sources say... We spoke to...").

- If the fact check is about a claim by a site or page that we have repeatedly fact checked in the past or about a topic that we have written about before we may also include more information about it + links to earlier fact checks ("We wrote about reallyreliabletotallynotfakesite.com before, it is run by spammers who...").

There are also some key principles we ask our writers to adhere to:

- Always provide links to the original story or source so our readers can verify we are properly representing what is said there.

- All links to information that is important for (dis)proving the claim should be backed up on archive.org and backup links should be provided in the story. I.e. if a story links to a report it should be linked to like this: "as you can read in this report (archived here)".

- Stick to the facts that are important for (dis)proving the claim and avoid giving too much background info that is not relevant for doing that, especially on deeply partisan issues. When checking if a number in the gun control debate (or about terminating pregnancies or about nuclear power or any controversial subject) is really x% or not, there is no need to include quotes from people or groups saying why that is a good or bad thing or how much it *should* be or how much it has historically been and why that was better or worse. People who want to know if something is good or bad can read about that on other websites or in opinion sections. People who want to know the latest news or the full history about a topic can check Google News or Wikipedia. Our site is there for people who just want to know if something is true or not.

No standardized rating scale

Lead Stories does not use a standardized rating scale or score to rate claims on our website. When we investigate a false or misleading claim we simply aim to explain what exactly is wrong with it and why. It would only be a source of confusion to also attempt to add a score, rating, number or a standardized description to say precisely how wrong it is. What is the difference between "half wrong", "partly real" or "mixed"? Is a claim that is 72% false really that much worse than one that is 28% true? Are five "TruthPoints" really better than four and what does that one point difference mean?

Most of our readers don't care or don't have the time to worry about distinctions like that.

They just want to know if that story they saw online is true or not. So we do our best to tell them.

About us

Lead Stories is a fact checking website that is always looking for the latest false, deceptive or

inaccurate stories (or media) making the rounds on the internet.

Spotted something? Let us know!.

Lead Stories is a:

- Verified signatory of the IFCN Code of Principles

- Facebook Third-Party Fact-Checking Partner

- Member of the #CoronavirusFacts Alliance

Follow us on social media